Americans are deeply in debt. In the fourth quarter of 2023, total household debt increased by $212 billion to reach $17.5 trillion, according to a report by the Center for Microeconomic Data.

Debt is linked to lower life expectancy, higher mortality, depression, high blood pressure, and forgone medical care. Debt and resulting bad credit scores can impact a person’s ability to secure housing, employment, and medical care. And it has a disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities, contributing to the perpetuation of intergenerational and structural inequity.

When debts are not paid — as is the case for the one-in-three U.S. adults who have a debt that has been turned over to a debt collection agency — the consequences can be severe and may include garnishment of wages, bank account seizure, or even criminal punishment. Despite the severity of these potential outcomes, debt collection lawsuits are overwhelmingly skewed in favor of plaintiffs suing to recover the debt.

Laws governing the debt collection lawsuit process vary widely across the United States, and even within a single state depending on the type of debt, court venue, or amount in controversy.

To that end, the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law has teamed up with The Pew Charitable Trusts to begin tracking state laws that regulate debt collection lawsuits. The data, released on February 14, 2024, provide a comprehensive overview of statutes, regulations, and court rules governing debt collection lawsuits that were in effect as of January 1, 2023, in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Through this research, we’ve identified laws in 41 states and the District of Columbia that specifically govern debt collection lawsuits. But these laws vary greatly: some states have debt lawsuit-specific laws that govern just one or two particular aspects of the process (such as statutes of limitation, or venue), and debt collection lawsuits in those states are otherwise governed by generally applicable civil procedure laws. On the other hand, a few jurisdictions have more comprehensive sets of laws that aim to specifically address issues unique to the debt collection lawsuit process and cover several stages of the court proceedings.

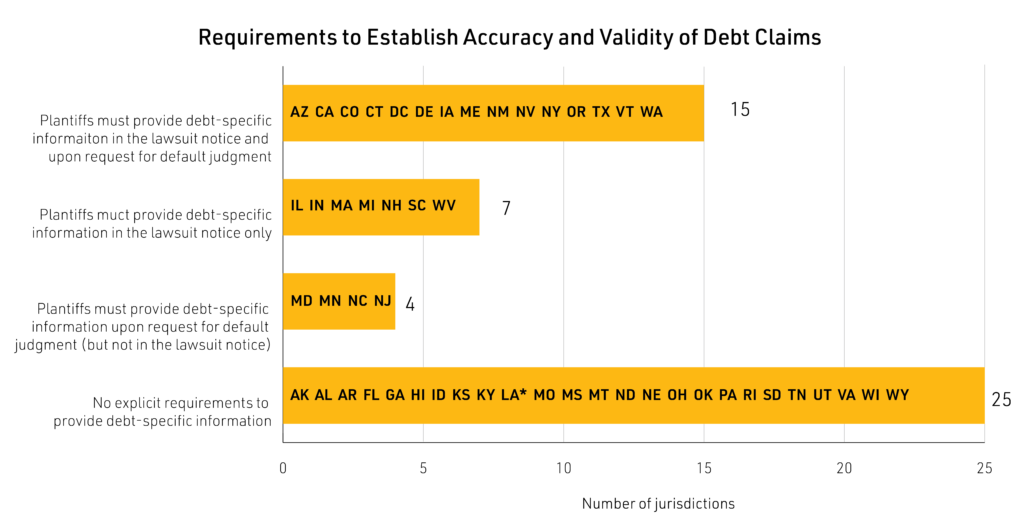

Just more than half of jurisdictions have laws that could potentially address the imbalance of power and outcomes in debt collection lawsuits by requiring certain plaintiffs (often just debt buyers or plaintiffs bringing consumer debt claims) to provide specific documentation to support the accuracy and validity of debt claims.

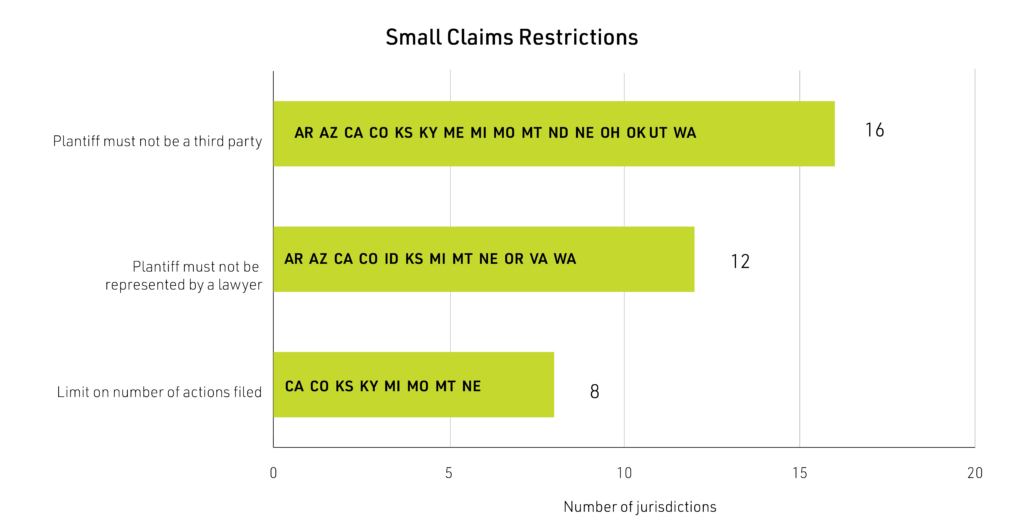

Even beyond these documentation requirements, the laws and rules that apply to a debt collection lawsuit can vary significantly depending on the court in which the claim is brought. Lawsuits brought as small claims actions are typically subject to less formal and more relaxed rules, which may be easier for unrepresented defendants to navigate — but may also make it easier for debt collectors to obtain default judgments. Several states deter consumer debt collectors from filing in small claims court through various restrictions: 16 states prohibit third parties (such as debt buyers or assignees) from filing in small claims court, 12 states prohibit plaintiffs from being represented by a lawyer in small claims court, and eight states impose a limit on the number of small claims actions a single plaintiff can file per week, month, or year. On the other hand, seven states and the District of Columbia require all civil claims (including debt claims) under a specified amount to be filed as small claims.

The data, which are free and open access, offer an essential look at the landscape of debt collection litigation laws and can guide policymakers, advocates, and others as they work to shape a more responsive and reasonable environment for consumers.

In particular, evidence suggests that certain reforms may improve outcomes for consumers and mitigate the imbalance of power in debt collection lawsuits. Legal experts and consumer advocates have recommended several policy reforms, including requirements such as those in the Uniform Law Commission’s model Uniform Consumer Debt Default Judgments Act. Once those reforms are implemented it’s up to the courts and other officials to implement and enforce them. And then we need to study them to see if they’re working!

Given the wide variation of these laws across jurisdictions and even across different court systems within a single jurisdiction, a full-scale legal epidemiological study using policy surveillance data could result in robust comparative evaluations of the law’s effect across jurisdictions and over time.

This blog first appeared on the Bill of Health blog from the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

Explore the research at LawAtlas.org and read our policy brief, which offers an in-depth analysis of the landscape.