By Jon Larsen and Sterling Johnson

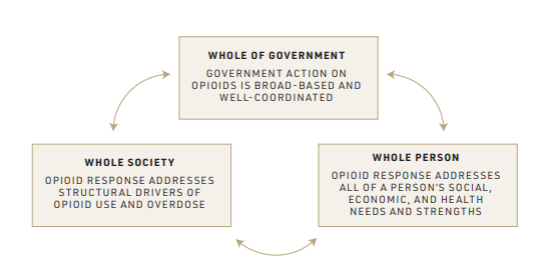

Addressing the opioid crisis cannot stop at providing better access to treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), expanding and enhancing harm reduction efforts, and reimagining the role of law enforcement, as explored previously in this blog series. The response must go further to make treatment and harm reduction more effective, by acknowledging the opioid epidemic as a reflection of the conditions of the whole society, identifying those conditions, and addressing them head-on. A whole-person response to OUD and other substance use disorders needs a well-coordinated whole-of-government response to address myriad societal issues that are critical to effective drug treatment, including, but not limited to, housing, education, economic development, and tax policy.

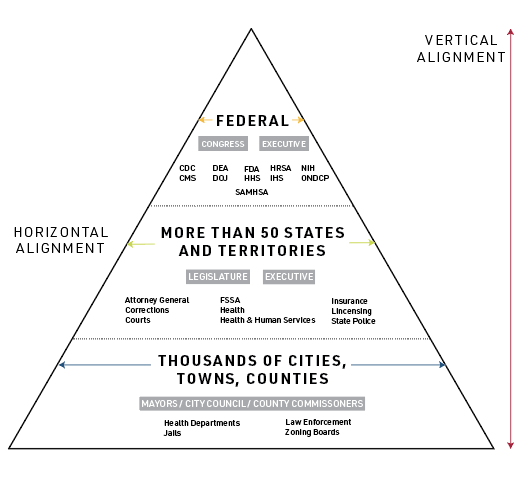

With support from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE), public health law experts from Indiana University McKinney School of Law and the Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research at the Beasley School of Law recently embarked on a systematic review of US drug policy using a whole-of-government (W-G) approach to assess where these misalignments are occurring among different agencies at the same level of government (referred to as horizontal W-G), and across different levels of government (referred to as vertical W-G). It ultimately provides a tool to address these misalignments directly.

From that work we identified and published 84 opportunities for US drug policy reform at the federal, state, and local levels across four domains: drug policing, harm reduction, social determinants of health, and health care.

The sixth report in the six-part series, which is focused on social determinants of health explains, “…if the health system and policymakers don’t start to methodically address the root causes of our opioid epidemic, with individual patients and with our whole society, the United States will continue to fail to stem the tide of drug-related harm. No amount of dealing with symptoms will be as effective as preventing the disease in the first place. Even the objection that changing social determinants will take too long fails when we consider that we have been throwing resources at symptoms for more than two decades without success.” The figure below illustrates the interaction between W-G coordination, societal barriers to OUD care, and individual health needs and strengths, which must all be considered in order to more effectively address the opioid crisis.

The eight opportunities below represent shovel-ready actions that could be taken to address social drivers of the opioid crisis.

To access the other nine opportunities regarding social determinants of health and to learn more about the rationale behind these opportunities, visit https://phlr.org/product/legal-path-whole-government-opioids-response

Federal Government Opportunities:

- CMS can encourage states to take advantage of optional Medicaid benefit categories that serve those with OUD/SUD such as rehabilitative or case management services, 42 U.S. Code § 1396n and apply for § 1115 waivers identified as supportive of substance use prevention or treatment and care transitions for incarcerated persons.

- HUD can amend 24 CFR §982.553 to narrow public housing exclusions linked to drug use to situations in which a person’s use of illegal drugs is causing observable harm to the premises or the community, and tighten key definitions to better guide local public housing agencies.

- Congress can enhance the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (26 U.S. Code § 32) by making the tax credit monthly.

State Government Opportunities:

- States can increase expungement rates by amending laws to apply automatic expungement to minor drug possession convictions and seal the records. See N.Y. Crim. Pro. § 160.50 which automatically expunges certain cannabis possession and sale records.

- States can remove cash bail requirements, especially for low-level offenders in pretrial detention, See Washington D.C., Bail Reform Amendment Act of 1992 that ended cash bail for most justice-involved individuals.

- States can establish minimum wage laws to a level sufficient to allow a full-time worker to rise above the poverty line and obtain stable housing. See N.J. Stat. §34:11-56a et seq. States can also remove barriers to local governments setting a livable local minimum wage. See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 8-6-10.

Local Government Opportunities:

- Local governments can provide sufficient funding for municipal and local court operations, and can strictly limit excessive fees and fines. See, e.g., San Francisco Ordinance Number 131-18, which eliminated county criminal administrative fees, such as probation fees, electronic monitoring, and booking fees.

- Local governments can provide temporary guaranteed income programs. See Stockton, California’s SEED Program, providing no-strings-attached guaranteed income of $500 monthly for 24 months.

As we explain in part six of the project, “A person with an opioid or other substance use disorder may have many other challenges as well as countervailing strengths and resources for coping and returning to full well-being.” It is in identifying resource gaps and structural factors that individual drug users face, like homelessness or lack of mental healthcare, that we can begin to systematically address those issues through changes to the law.

The legal opportunities highlighted above address federal, state, and local policy misalignments that have resulted in among other things, limited access to health care, unstable housing, limited economic opportunity, lack of employment, and harmful criminal records for minor offenses, all of which exacerbate the opioid crisis. Each opportunity represents a different but related lever, which work best when done in concert — other opportunities are explored elsewhere in this blog series.

Examples of federal, state, and local government agencies that should interact to promote a Whole-of-Government approach[/caption]

Jon Larsen, JD/MPP, is a Legal Program Manager at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Sterling Johnson, JD, MA is a Research Analyst at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law and a Ph.D. Student at Temple University’s Department of Geography.

This blog first appeared on the Bill of Health blog from the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.