People who need opioid use (OUD) treatment in the United States are often not receiving it—at least two million people with OUD are experiencing a treatment gap that prevents or hampers their ability to receive life-saving care and support. This reality reflects structural, policy, and legal misalignments common to the entire US health care system, but that are especially present for behavioral health needs like substance use, and are exacerbated by other challenges related to stigma, lack of employment, and fragmented or nonexistent care coordination.

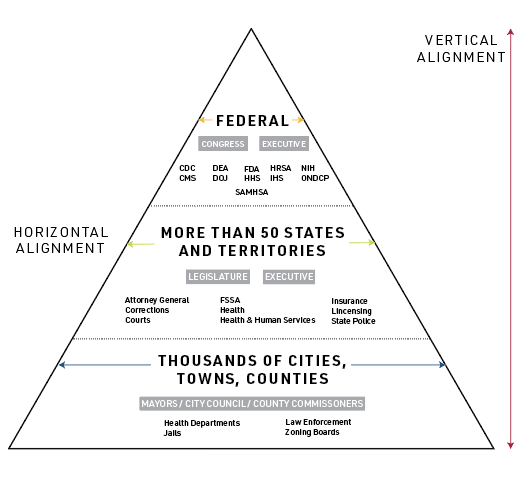

With support from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE), public health law experts from Indiana University McKinney School of Law and the Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research at the Beasley School of Law recently embarked on a systematic review of US drug policy using a whole-of-government (W-G) approach to assess where these misalignments are occurring among different agencies at the same level of government (referred to as horizontal W-G), and across different levels of government (referred to as vertical W-G). It ultimately provides a tool to address these misalignments directly.

Examples of federal, state, and local government agencies that should interact to promote a Whole-of-Government approach

From that work, we identified and published 84 opportunities for US drug policy reform at the federal, state, and local levels across four domains: drug policing, harm reduction, social determinants of health, and health care.

The five opportunities below represent shovel-ready actions that could be taken to support a commitment to improving access to equitable OUD care and reducing barriers to prevention, treatment, and recovery — all actions essential to overcoming historical stigma and building an integrated health care system that better serves people who use drugs and transcends regulatory hurdles to treatment advanced by the “war on drugs.”

To access the other 34 opportunities for improved health care for people with OUD and to learn more about the rationale behind these opportunities, visit https://phlr.org/product/legal-path-whole-government-opioids-response.

Federal Government Opportunities:

“The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) moved too slowly in allowing mainstream prescribing of buprenorphine and methadone, creating unnecessary barriers for emergency room and general practitioners,” the report explains.

DEA has done little to reduce the appearance of agency capture by the Opioid Treatment Program (OTP) industry, while FDA was years behind the evidence in approving over-the-counter naloxone. These and other impediments are remnants of the “war on drugs” and are both the product of and the nourishment for moral defect judgments that perpetuate stigma against people with OUD.

To counter these concerns:

- The federal government can designate a single source of contact for the states within Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) to provide horizontal alignment across federal agencies and work with the states in aligning vertical implementation through amendments to the Office of National Drug Control Policy Reauthorization Act of 1998, 21 U.S. Code § 1701 et seq.

- Congress can extend the liberalization (Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (Public Law 117-328) § 4133) of telemedicine policies beneficial in the treatment of substance use and other behavioral health needs (including qualifying providers, geographic and originating site restrictions, and audio-only telehealth services) beyond the sunset date of December 31, 2024. The nation’s experience with COVID-19 demonstrated the need for increased telemedicine options for the treatment of substance use, especially in suburban and rural areas where health provider closures may severely limit access to care.

State Governments:

- States can enact legislation to limit or ideally remove prior authorizations for SUD services and medications such as that passed in New York, see New York Insurance Law § 4303(l-1)(A)

- States can address gaps in coverage from citizens returning from correctional settings by applying for Section 1115 waivers to expand Medicaid prerelease services. See e.g., California’s 1115 waiver (pages 1-9 have an overview of prerelease services).

“If…. we can reform jails and prisons from places of withdrawal and abstinence to treatment and recovery, we need to better connect their populations with the outside world. Death from overdoses is the leading cause of death in the immediate post-release period,” part four of the report states. It goes on: “Connecting people released from prisons and jails with health care and other social supports such as safe housing and employment is a priority.”

Local Governments:

-

Local governments can enact ordinances requiring pharmacies to maintain stocks of buprenorphine and naloxone. (See, e.g., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Municipal Code § 9-637). Studies have found that pharmacies sometimes choose to simply not stock certain medications for people who use drugs. Philadelphia is the only county that has passed such a stocking requirement, but other jurisdictions should look into how to operationalize the stocking of essential medications such as buprenorphine and naloxone.

The legal opportunities highlighted above, when considered together, facilitate access to OUD treatment, from potential direct federal coordination of OUD treatment response through ONDCP to marshal resources at the federal level and direct them to the states, to liberalization of federal telemedicince options for OUD, to removal of prior authorization for OUD and expansion of Medicaid services for justice-involved individuals returning to the community at the state level, and the potential of mandated pharmacy stocking of buprenorphine and naloxone at the local level. Each opportunity represents a different treatment challenge solution, which are amplified when done together—other opportunities regarding drug policing, harm reduction and social determinants of health will be considered in subsequent blog posts.

Jon Larsen, JD/MPP, is a Legal Program Manager at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Sterling Johnson, JD, MA is a Research Analyst at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law and a Ph.D. Student at Temple University’s Department of Geography.