By Sterling Johnson

Not since the 1960s have we seen the terms of Black history been this contested among legislators and school districts. Three years after the George Floyd riots and our own national reckoning, we continue to watch explicit attacks on the teaching of critical race theory, but also more integration of Black history into the national story — with Florida’s legislative history serving as a primary landscape for this cultural battle.

In June 2020, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed legislation requiring schools include the Ocoee Election Day massacre in the curriculum, along with other concepts like the Holocaust and antisemitism. In 1920, the Ku Klux Klan rode through Ocoee, Florida, located 10 miles west of Orlando, warning all Black citizens against voting in the coming election. Two Black men attempted to vote and were denied. In retaliation for attempting to vote, the Ku Klux Klan burned 24 homes and murdered 50 Black citizens causing a mass exodus from the town. Some Black Floridians had never heard of this event, an act of terrorism is known as the Ocoee Election Day Massacre. Such positive movement in civil rights and inclusion of diverse histories led to backlash, with Florida again taking the spotlight, this time in a negative direction.

About a year later, Governor DeSantis was in the news again for signing the Individual Freedom Act, also known as the Stop Woke Act, meant to prohibit the teaching of critical race theory. It is a broadly written law seemingly intended to touch many facets of public education and applies to all levels of schooling, including post-secondary institutions such as the University of Florida and Florida State University. One professor simply cancelled classes titled “Race and Social Media” and “Race and Ethnicity” as he was up for tenure in the fall and did not want to risk falling outside the guidelines set by the University’s administration. Some professors have stopped teaching critical race theory altogether. Though the bill is currently blocked from enforcement, the impact of its intent is being felt as Florida universities provide guidelines to their professors due to funding cut fears.

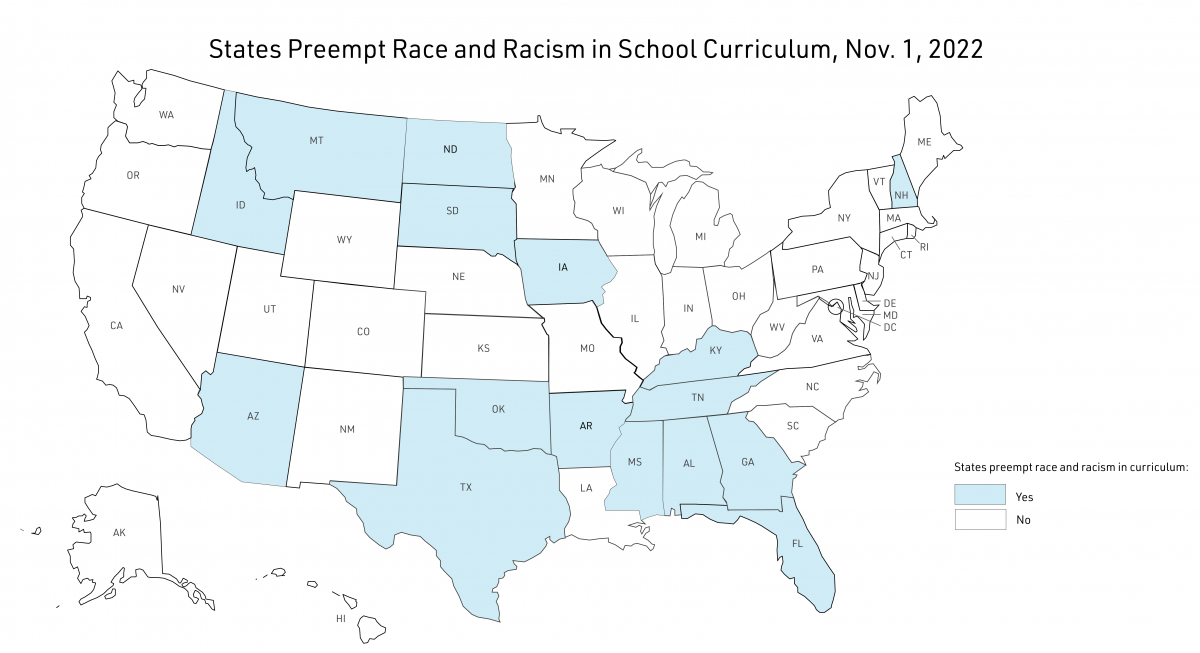

Many other states have passed similar bills that not only target colleges and universities but also K-12 education. In our research on the nature of state-level preemption across 15 domains, we examined the ways states are using law to address local control of policies that teach race and racism in K-12 education.

As of November 1, 2022, 16 states had passed laws restricting the ability of educators to talk about race and racism in the curriculum. In 2019, only one state had such law. All 16 states provide details of the specific concepts that cannot be taught; five states explicitly prohibit teaching “critical race theory.”

Seven states impose penalties for discussing race and racism in the classroom. Two of those states name specific penalties for teachers (Arizona and New Hampshire) and principals (New Hampshire).

Some of these laws focus on countering the 1619 Project’s central thesis that the United States (U.S.) is an inherently racist country and that the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1619 was critical to its founding. The primary concern of these laws is that students are being indoctrinated into a way of thinking that is antithetical to the traditional national story.

Looking beyond preemption, five states — Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, Florida and South Dakota — have passed laws banning teaching “critical race theory” outright in Public Colleges. Instruction around certain ideas is banned, for example, such as the idea that one race is responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race; that a person should feel discomfort, shame or guilt or any other psychological distress on account of one’s race; or that meritocracy was created in order to oppress members of another race. Florida’s law also grants a private right of action for any parent or student if they believe that a professor or university has breached the Stop Woke Act.

There are some positives: while critical race theory has been under attack, some cities have attempted to integrate it into the broader curriculum. Kentucky and Texas also added new Black history courses in 2020 and Virginia has gone a step further, creating the African American History Education Commission that made recommendations to change the U.S. History curriculum. These changes were implemented in fall 2021. However, even these gains were uncertain, as in 2022, Virginia’s newly elected Governor signed an Executive Order outlawing teaching “critical race theory” and “divisive topics.”

Black history scholar LaGarrette King has presented a framework for educators to understand why Black history matters. Generally, even teaching about Black history, slavery, Jim Crow, and discrimination helps to reify the subordinate role of Black Americans, and reinforce the white historical lens that supports the need for Black Americans to show gratitude for the liberation out of poorer African conditions enabled by the Atlantic Slave Trade. King’s framework focuses on Black joy and love, Black agency and resistance against oppression, and contextualizing the African continent in global history.

These teachings subvert dominant paradigms of Black inferiority and helps ground Black students in their own sense of self. Black history integration in U.S. history can encourage equity in schools, as it shows that U.S. society cares about Black history and Black people’s humanity. It may be a significant symbolic step toward reaching racial equity in all policies.

Sterling Johnson is a Law and Policy Analyst at the Center for Public Health Law Research and a PhD student in Temple University’s Department of Geography and Urban Studies.

The State Preemption Project was a collaboration between the Center for Public Health Law Research and the National League of Cities. Support was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.