There is a well-established whole of government response to drug policing centered around the “war on drugs.” However, the existing response is largely built on flawed policies that have resulted in mass incarceration, structural racism, and lagging improvements in treatment and harm reduction related to the opioid crisis. Policy changes must be considered to replace acknowledged failures and reimagine the whole of government response to drug policing.

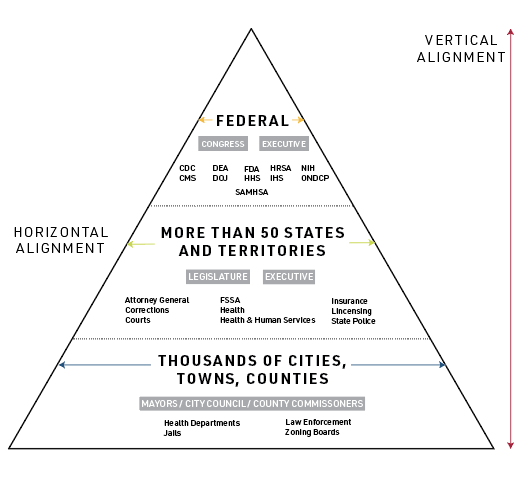

With support from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE), public health law experts from Indiana University McKinney School of Law and the Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research at the Beasley School of Law recently embarked on a systematic review of US drug policy using a whole-of-government (W-G) approach to assess where these misalignments are occurring among different agencies at the same level of government (referred to as horizontal W-G), and across different levels of government (referred to as vertical W-G). It ultimately provides a tool to address these misalignments directly.

From that work, we identified and published 84 opportunities for US drug policy reform at the federal, state, and local levels across four domains: drug policing, harm reduction, social determinants of health, and health care.

The third report in the six-part series, which is focused on drug policing explains, “The primary W-G task that lies ahead for both federal and state governments is to recognize what the evidence has been telling us, that the ‘war on drugs’ is a failure, and escalation will only double-down on that failure. A coordinated extraction from our present landscape will require the actors to abandon the ‘moral defect’ view of those with substance use disorders and accept that its causes are similar to those that lie behind other chronic diseases.”

The seven opportunities below represent shovel-ready actions that could be taken to reimagine drug policing response to the opioid crisis to specifically address underlying policy failures.

To access the other five opportunities regarding drug policing and to learn more about the rationale behind these opportunities, visit https://phlr.org/product/legal-path-whole-government-opioids-response

According to the report, “Stepping back from our current approach to drug policing is simple in concept but complicated in execution. Politically it will be an immense task and, initially at least, will be measured in incremental rather than fundamental progress. It will be important to formally recognize not only the failure of the ‘war on drugs’ but also its toll on the physical, mental, and familial health of those it swept up.”

Federal Government Opportunities:

- Congress can amend 18 U.S. Code § 983 (civil forfeiture proceedings) as proposed by the Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration Act of 2023 (FAIR), H.R.1525, 118th Congress (2023-2024), to change the burden of proof to “clear and convincing” evidence and reduce numerous abuses commonly associated with drug arrests.

- Given the resources required and lack of general deterrence, DOJ can instruct federal prosecutors to abandon “Charging the Death,” 21 U.S.C. § 841(b) (1)(C), in cases of low-level dealers or users who sell some of their own drugs.

State Government Opportunities:

- States can abandon civil forfeiture in minor drug cases (See e.g., N.M. § 31-27-4).

- States can repeal or amend their mandatory minimum sentencing laws to stop incarcerating hundreds of thousands of nonviolent, low-level drug offenders, often with no chance of parole.

- States can amend their drug possession laws to make offenses at most a misdemeanor (e.g., Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-1.3-501) and enact other reforms to encourage probation or diversion sentencing (e.g., Massachusetts General Laws Part I Ch. 94C, § 34).

- States can reform child welfare laws and enforcement so that pregnant drug users are not afraid to seek prenatal and other care.

- States can remove barriers to layperson immunity (including “Good Samaritan”), such as requirements for calling or providing identities to law enforcement. See e.g., Indiana Code § 16-42-27-2(g).

As we explain in part three of the project, achieving a transformed state requires rethinking the role of law enforcement and looking beyond the current crisis as one solved by public health strategies. As noted in the drug policing report reforms supporting a commitment to public safety initiatives such as providing amenity in civil spaces, teaming up with social services, and leveraging behavioral health skills to replace arrests and incarceration are a strong counterpoint to the idea that reform shows weakness on fighting crime. These reforms amount to a reduction of the role of police in addressing what are essentially societal problems as has been suggested by Human Rights Watch .

The legal opportunities highlighted above address federal and state drug policy misalignments that have resulted in mass incarceration and instead reimagine law enforcement response to facilitate diversion to healthcare intervention versus arrest, prosecution, or civil forfeiture, and attempt to enhance trust by removing barriers to people who use drugs from accessing care, whether related directly to an overdose or for general mental or physical health. Each opportunity represents a different but related lever, which work best when done in concert — other opportunities regarding harm reduction and social determinants of health will be considered in subsequent blog posts.

Examples of federal, state, and local government agencies that should interact to promote a Whole-of-Government approach

Jon Larsen, JD/MPP, is a Legal Program Manager at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Sterling Johnson, JD, MA is a Research Analyst at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University Beasley School of Law and a Ph.D. Student at Temple University’s Department of Geography.

This blog first appeared on the Bill of Health blog from the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.